Monkeys and Pedestals: Why We Often Build What Nobody Uses

June 16, 2025

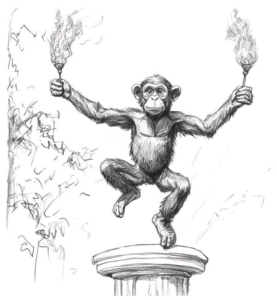

Imagine your new venture involves teaching monkeys to juggle flaming torches while standing on pedestals in the park. This kind of business should generate substantial revenue. You have a project with two components: building pedestals and training monkeys. Does it matter which you tackle first?

If you’re an engineer, you’re probably already sketching the pedestal design. Maybe you’ll make it from oak planks? Add some lighting? Integrate it with blockchain? Meanwhile, the monkey sits in its cage, not even looking at the torches.

This sounds absurd, but it’s exactly how we operate. The reason is simple: pedestals are safe. We know how to build them. They deliver tangible results—you can measure progress from day one with lines of code, demo something in a month, show management your progress.

If you build a great system that nobody uses, maybe it’s the market’s fault, but you did your part. But if you can’t teach the monkey to juggle, the failure becomes undeniable.

In crypto projects, the monkeys are equally brutal: Does anyone need this? Are they willing to pay for it? Is our solution significantly better than what already exists? Yet we build another DEX, another faster L1. Once we build it, users will surely come.

The Sunk Cost Trap

But this isn’t just a prioritization problem. Once we’ve invested heavily, it becomes extremely difficult to abandon the investment. The more we’ve invested, the harder it gets. We’ve learned this lesson repeatedly at Empirica over the past few years.

Behavioral economists call this the sunk cost fallacy.

Real-life example: friends offer you a ticket to see a great band. You check the forecast—it’s going to rain and be cold. You’d probably decline because you don’t want to freeze and get soaked all evening. But what would you do if you’d bought the ticket yourself for $50? What if you paid $500? Would the rain still be such a problem? It’s the same concert. The same weather. The only difference is how much you’ve already spent.

Rationally, sunk costs don’t matter—the money is gone either way. Only future benefits versus future costs should matter.

In projects, this works identically, except the stakes are higher. We’ve invested six months building a subsystem. It’s not working as it should, but maybe one more month? Maybe two? Maybe an architecture change while we’re at it?

In investing, this mistake is particularly deadly. We buy, the price drops, we hold. We wait for it to bounce back. As if the investment owes us something. But the rational question is: would we buy this today at the current price? Does the investment still have positive expected value? If not, holding is equivalent to buying anew.

Kill Criteria

We get into real trouble when we start a project by building the pedestal. We’ll incur costs and find it very difficult to back out, while building the pedestal won’t teach us anything about whether we’re heading in the right direction.

Since human psychology makes it hard to abandon losing projects, we must do two things:

– in the first step of any project, define what the monkey is

– establish project abandonment criteria upfront, before emotions and sunk cost fallacy take control

Looking at the second point—proper kill criteria include both a state and a timeline:

– if after a quarter we’re not covering infrastructure costs, pivot

– if customer acquisition cost > 3x lifetime value, we don’t scale

– if we don’t have a working prototype by June, we’re done

It’s like a stop loss in trading. You set it when you open the position, not when you’re already losing.

For us, given competing priorities and numerous ongoing tasks, total project cost sometimes works better than deadlines. However, an implementation deadline may still be necessary, as deployment too far in the future might lose business relevance.

How to Recognize Your Monkeys

Returning to the first task— you should start every project by asking: “What must be true for this to succeed?”

The monkey is always something not entirely under your control. It’s an assumption about the external world, about other people, about the market.

Pedestals are things under your control. Code, architecture, documentation, processes. You can build them through willpower and hard work.

Monkeys require validation: Will customers pay? Will the strategy make money? Will users come?

Design the simplest possible experiment. And if the experiment’s result is negative—kill the project. This sounds brutal? It is brutal. But the alternative is months of building something that will never work.

Uniswap was the opposite example. Hayden Adams started with the question: will projects deposit capital in an Automated Market Maker and expose themselves to impermanent loss to enable investor trading? He built the simplest possible version—a few hundred lines of code. Only after convincing himself that people started using it did he invest in UX and marketing. The UX for Liquidity Providers still needs considerable investment, but they should be able to handle that pedestal.

Shifting Perspective

Stop thinking about projects as building. Start thinking about them as learning.

Every project is a hypothesis. The question isn’t “what will we build?” but “what do we need to learn?”

When the monkey doesn’t learn to juggle, that’s not failure. That’s valuable information. You can look for another monkey or another way of teaching.

When you build a pedestal for a non-existent monkey, you only learn how to build pedestals. In a field that changes as rapidly as crypto, the ability to quickly kill bad ideas is as valuable as the ability to execute good ones.

Next time you take on a project, immediately head toward the pain and ask: where is my monkey? And how quickly can I test whether it will learn to juggle?

I came across the concept of monkeys and pedestals in Annie Duke’s book “Quit”. Highly recommend it—Annie was a professional poker player and has many brilliant insights about cognitive biases in decision-making. Essential reading for founders.

Btw, we help crypto teams finance monkey training by generating yield from their treasury.

Michal